Gundersen uses genome sequencing to monitor, track COVID-19 spread

As of Thursday, health officials reported six cases in Wisconsin of a more contagious COVID-19 variant that was circulating widely in the United Kingdom last year.

Those cases were identified through genome sequencing.

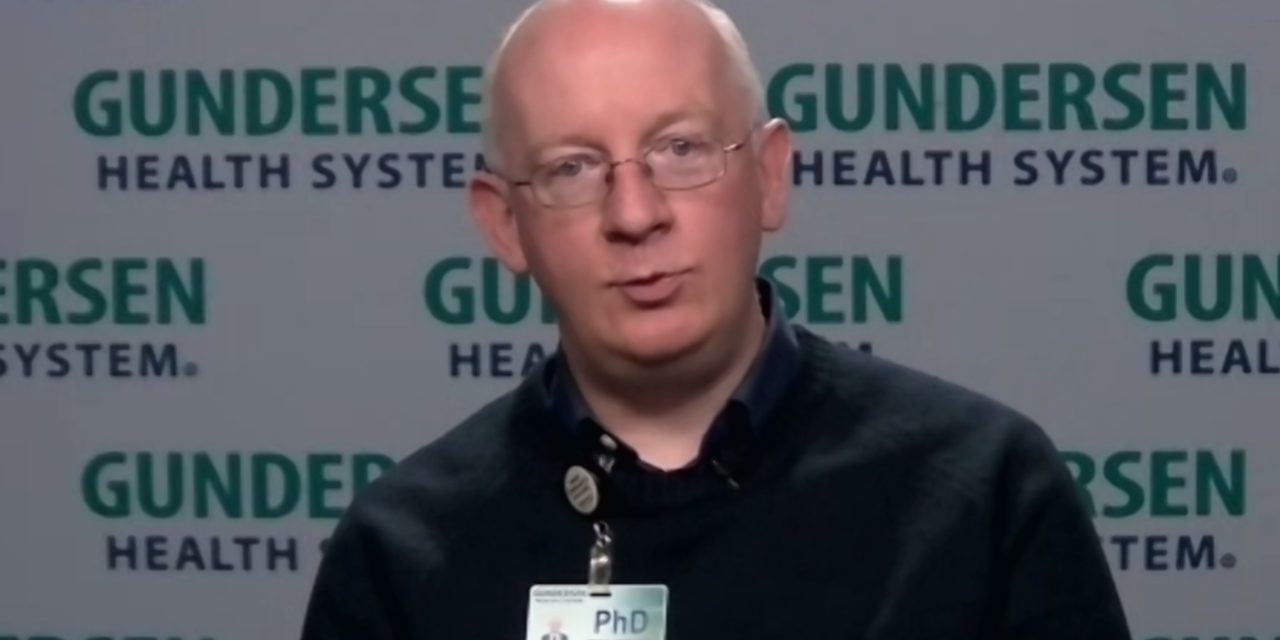

Paraic Kenny, director of the Kabara Cancer Research Institute of the Gundersen Medical Foundation, runs one of the handful of labs in the state sequencing COVID-19 specimens.

His lab was among the first to sequence the virus in the nation.

“We believed that understanding the genetics of the virus and tracking rigorously how it can move between populations would provide us with some additional means of mitigating its spread,” Kenny said in a recent interview with Wisconsin Health News.

Edited excerpts are below.

WHN: What COVID-19 variants are you looking for and why are they concerning?

PK: We’ve been sequencing COVID-19 here since March of last year. So we’ve sequenced more than 1,400 viruses so far. Mostly, up until recently, the variants we’ve been looking for have helped us to segregate out the genomes of the virus to understand which groups of people in the population are likely sharing common transmission chains and common risks.

But in the past month or two, we’ve become, like others have around the world, more concerned about some of these newer variants that have genetic mutations that seem to confer more high-risk properties on the virus. So the most prominent one probably is the B.1.1.7 that emerged in the U.K. and then quickly came to dominate the U.K. coronavirus landscape. It’s arrived in the U.S. with multiple introductions, most notably in Florida and in California, where it now comprises about 10 percent of all COVID-19 cases and is doubling at a rate of every 10 days. I think there was solid indication from the U.K. data that it was more transmissible and that’s certainly what we’re seeing here. So our concern is if and when it gets a foothold in Wisconsin, we’re going to see it overtake the other coronavirus strains that we have here and put more of our population at more risk because it seems to spread more efficiently.

The good thing about that strain is that it is quite susceptible to the vaccine. So we think as the vaccines roll out, more of our population should be protected against B.1.1.7. There are a couple of other strains where there’s probably more concern for lack of efficacy of the vaccine, which is something we’re also pretty concerned about. But we have not detected any of those so far in Wisconsin.

WHN: What have you been able to see in terms of sequencing?

PK: From the start in Wisconsin, back in March and April, we had a stay-at-home order. So we were sequencing the cases that were coming in. Typically, it would be someone who would have traveled to somewhere like New York City. They’d come home. They’d test positive. Their spouse would test positive. But public health would get involved very quickly. The family unit would be isolated. And most of these transmission trains didn’t go further than that.

The first striking outbreak we had in our region we detected in a meatpacking plant in Postville, which is a small town down in Iowa. So rather than having one or two viruses that were very similar, which had been our pattern up until then, all of a sudden we had five, 10, 15, 20 viruses, all from the same town, all being very, very similar. And it was clear very quickly that a meatpacking plant was the nexus of that outbreak. That allowed us to be really the first in the country to use genetics to look at the effective spread within a meatpacking plant environment.

But because we were sequencing across a very broad region – Gundersen covers 21 counties in western Wisconsin, southeastern Minnesota and northeastern Iowa, and we weren’t setting out to study meatpacking workers, we were just sequencing everything we could get – we then detected that exact strain that had been in the meatpacking plant over the following weeks in many towns across seven counties of these three states. That was important information because up until then, people were really looking at meatpacking plants, for example, as kind of a risk factor in isolation. There are a lot of workers crammed in there. It’s a risk for spread. But the appreciation that disease from there can spread out into wider communities and people who have no apparent connection to a meatpacking plant really wasn’t very well established.

Similarly in October, we sampled a lot of cases from college students in La Crosse. We had a big outbreak, with about 2,000 cases in the county in September alone. And we determined that that outbreak was driven mostly by two substrains. But then two to three weeks later, we started picking up cases in our nursing homes that were driven by the same strain that was circulated on these college campuses. So again, like with the meatpacking plant, the genetics allowed us to draw some pretty bright and clear lines between these outbreaks, which would have been a whole lot more challenging to draw using simple contact tracing and things like that.

WHN: Gundersen was quick to roll this out. What led to the early focus?

PK: I’m a cancer geneticist by training. So we’ve been using genome sequencing for a long time, but more focused on trying to understand the mechanisms that are driving the tumors in our patient population. So we had all of the equipment and much of the knowledge that we needed to sequence the virus. We just haven’t had a footprint in viral epidemiology before. But getting back to March when the first cases arrived in our region, there was a real sort of vacuum in leadership I think at that point at the federal level. The (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) had been incredibly, catastrophically slow to roll out testing. So it wasn’t at all clear that much help was going to come from anywhere. So we were thinking as an organization, as a research team, is there anything that we could do to potentially try to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on our healthcare organization, and more broadly on our patients and our region. So we felt that sequencing the virus was going to be a potentially useful way to do that. And it’s been great to see how widely since then this approach has been adopted across the country. We were just the 15th lab in the United States to report COVID-19 sequences, but there’s many more involved now and a much greater appreciation at the federal level, both at the CDC and in the Senate and in the White House that this particular approach was a really gap in the pandemic preparedness here and needs to be resourced more carefully.

WHN: How are you working with other sequencing efforts in the state?

PK: Of the three big efforts, the biggest one is run out of the (University of Wisconsin-Madison) by Professors David O’Connor and Tom Friedrich, who are professional virologists and have been in virus sequencing for a long time. There’s my effort here at Gundersen in La Crosse, which we came in to from a much more amateur perspective because we were not professional virologists. But we were really good at genetics and genomics, so we adapted to that pretty quickly. And then the Wisconsin State Lab at the Department of Health Services more recently got into virus sequencing. And even though they’ve come a little bit late, they’ve really done very well in recent months. The folks in Madison generally sequence a lot in Dane County and Milwaukee area. We cover a lot of the region around La Crosse. And then that frees up the state lab to focus on these areas of the state that are much less well covered by the more academic efforts.

WHN: Is there a need to increase the level of surveillance in the state?

PK: I think reasonable people would probably disagree about what the optimal percentage of cases we should be sequencing. Denmark is sequencing about 50 percent of cases. U.K. is doing really well as well. That’s probably a little bit higher than is necessary to be useful. So you get to the point of diminishing returns.

We’re doing great in Wisconsin compared to other states. We’re per capita the second highest sequencers of states across the nation. But we’re still in low single digits. I think pushing us up to somewhere between 5 and 10 percent would be a big boost to the utility of this across the state. And I think that’s particularly important with the emergence of these new variants that are coming in.